As part of the work on my dissertation, I research the different photographic representations of certain turning points and events in Chinese history and as far as events go, they don’t get any more iconic than the ’89 student protests on Tian’anmen square.

Today is the anniversary of the violent crackdown on the ’89 Democracy Movement (or vulgo Tian’anmen Square Protests) in Beijing and other cities. On this occassion I want to discuss a photobook released last year, which the library of the Asien-Afrika-Institut of Hamburg University was so kind to acquire just a few days ago, making it accessible for me:

Xu Yong 徐勇. Negatives. Dortmund: Kettler.

(ISBN 978-3-86206-529-5, bound copy 48€)

The Photographer Xu Yong 徐勇

According to the information provided in the book, Xu Yong was born in Shanghai in 1954 and is now living in Beijing.

Photographic works of his include:

Hutong 101 Photos 胡同101像, 1989

Opening Beijing 开放北京, 2001

Xiaofangjia Hutong 小方家胡同, 2003

Backdrops and Backdrops 布景与背景, 2006

Solution Scheme解决方案, 2007

18% Gray 十八度灰, 2010

This Face这张脸, 2011

The Book

The book itself is lavishly produced, the cover done in linen and protected by a clear plastic dustcover reminsicent of an oversized strip of 35mm film. This dustcover bears a negative print of the “Goddess of Democracy”, a statue made from plaster and styrofoam which the protesters erected on the square, directly vis-à-vis the portrait of Mao Zedong hanging on Tian’anmen.

The 64 negatives in the book are reproduced in a fantastic quality on thick, coated paper. Most negatives get their own page, with none printed across the gutter. This makes it possible to concentrate on appreciation of the pictures. Some of them are printed smaller, in groups on one page, but they are still large enough to clearly make out the scenes. The negatives are accompanied by three short essays written by Shu Yang 舒陽, Gérard A. Goodrow and Martin Rendel. Especially outstanding is the one by Shu Yang discussing the use of the negative as a part of the photographic process and – perhaps as an answer to problems posed by digital imaging – as a possible final product of photographic creation.

The Photos

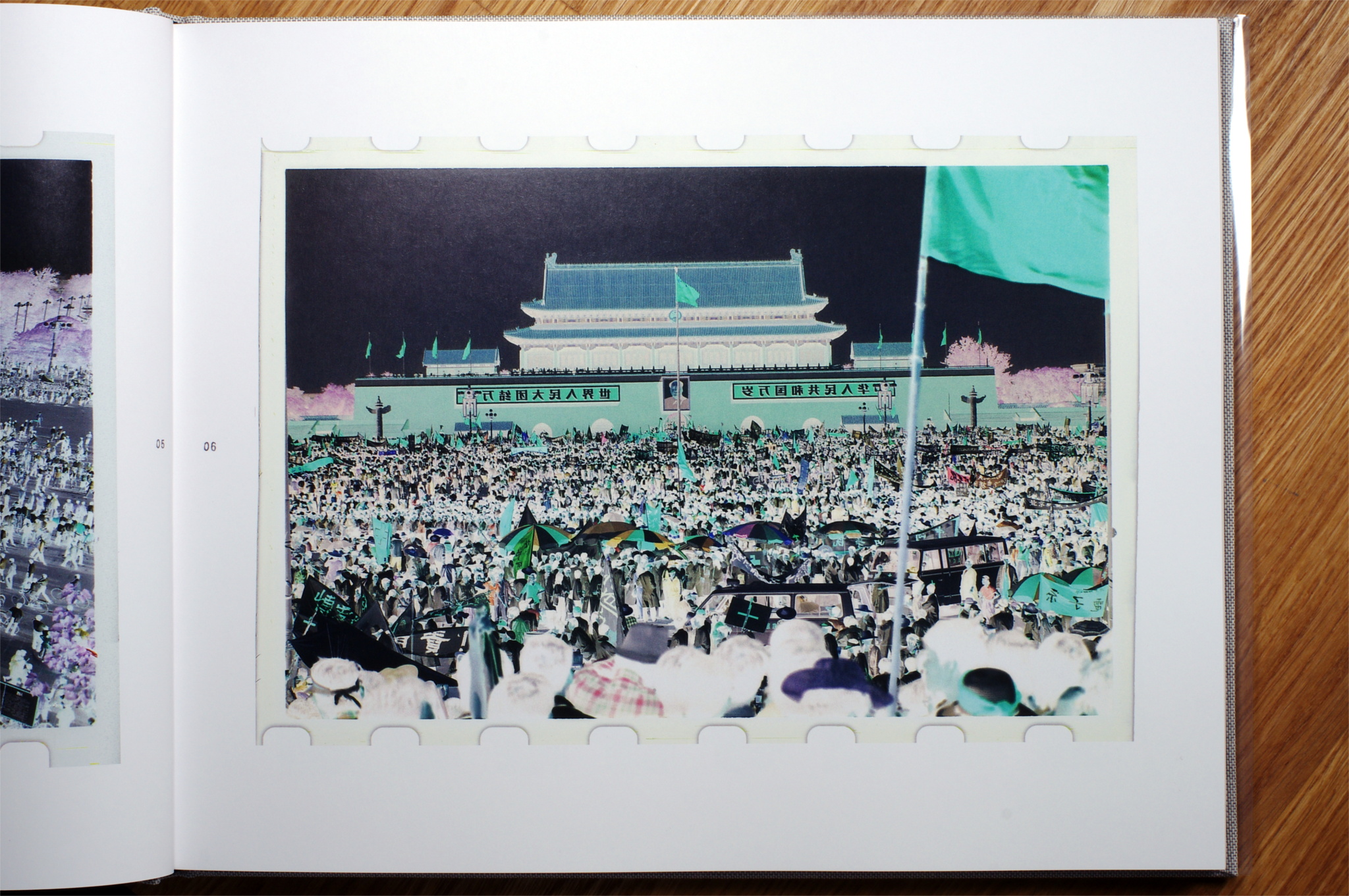

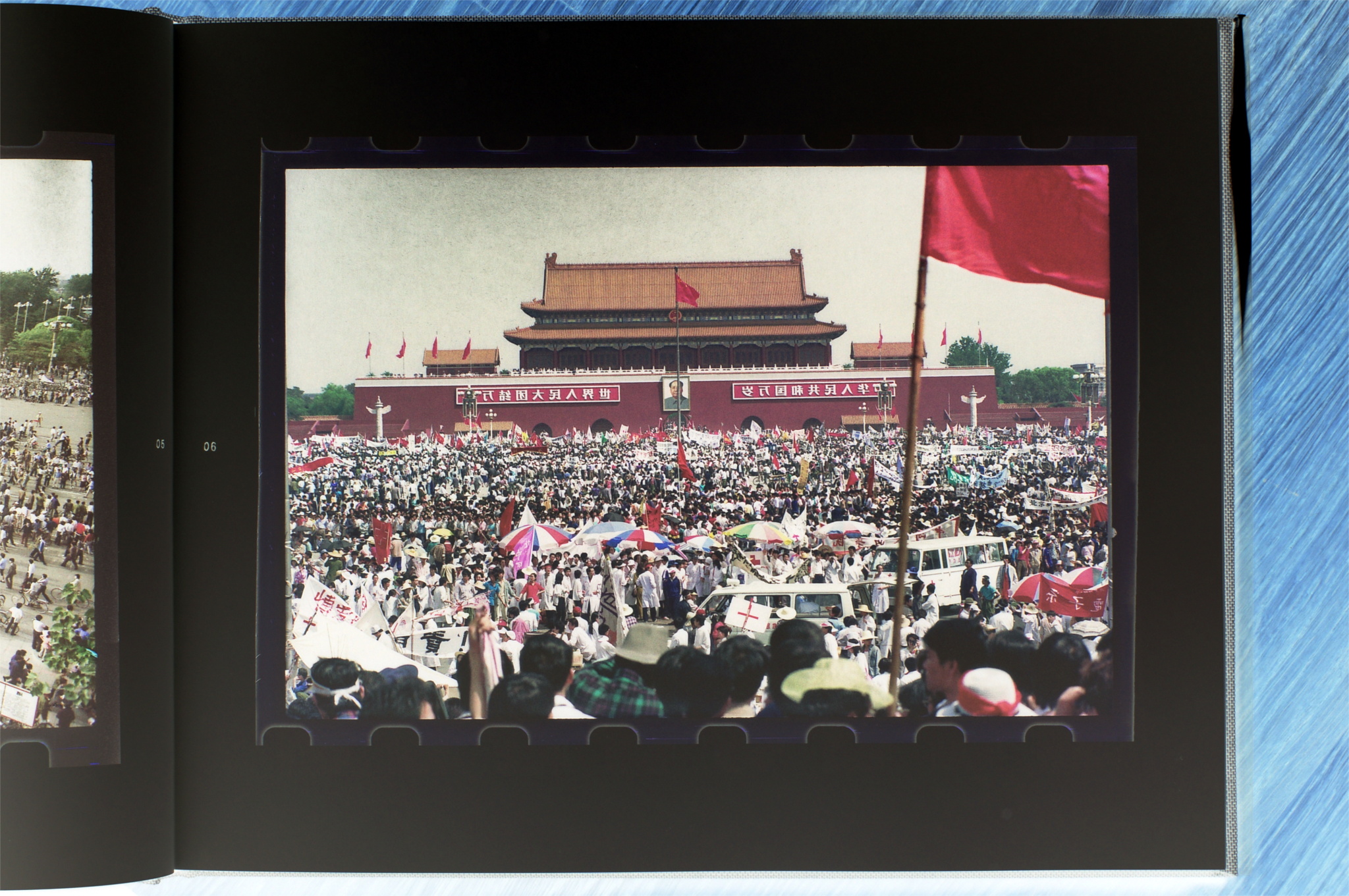

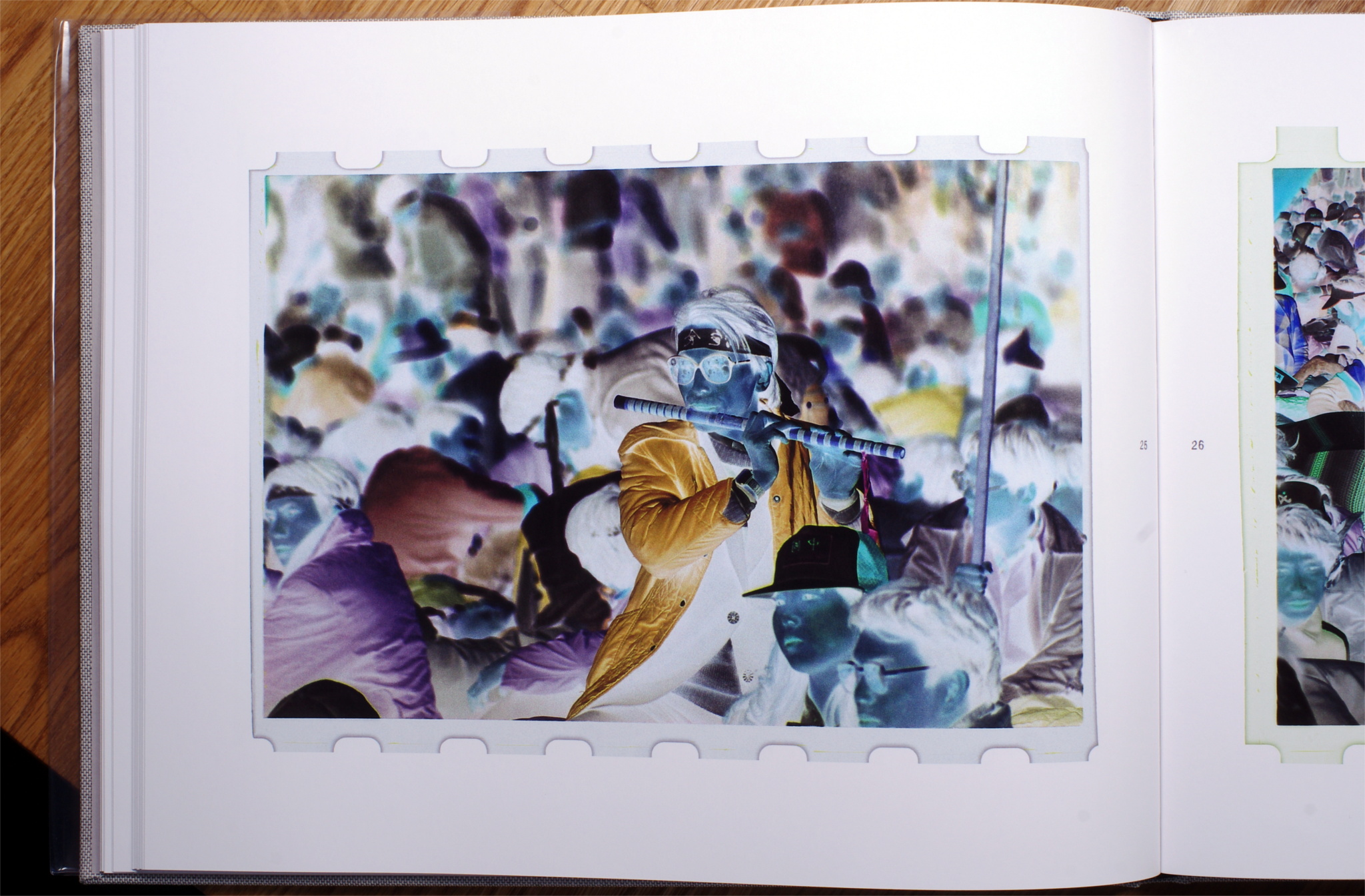

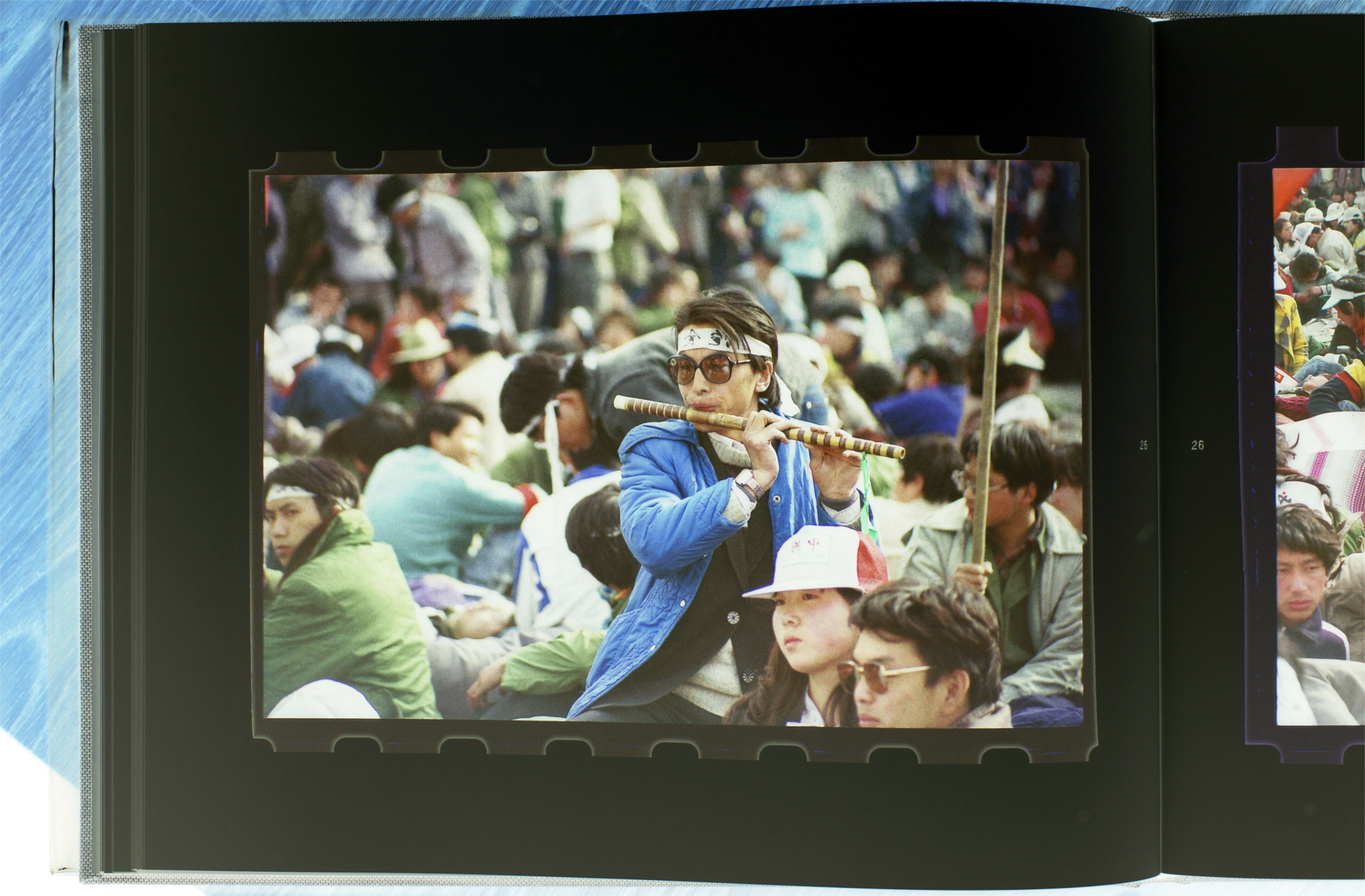

The photographs in this book all show different scenes of the protests on Tian’anmen Square, with the catch that they are all reproductions of part of the negative film strips, complete with sprocket holes on the upper and lower border of the pictures, showing the picture in its original, negative form, basically the way the camera recorded them. They have even been reproduced as mirror images, the way the light from the lens draws them in the camera, though the authors didn’t go as far as to print them upside down, which would ultimately be correct. (The picture drawn by a camera shows an inverted image: Left becomes right, and up becomes down.)

To allow the non-photographer to make sense of the scenes, the author suggests using a smartphone or tablet with the colours of the screen or camera-app inverted, thus revealing the picture “hidden” in the negative. This brings the pictures to live and adds a sense of immediacy and viewer participation, which is acknowledged as intentional in Shu Yang’s accompanying essay.

My Impression

Originally I just wanted to lay hands on this book as an example of “recently published photographs of the Tian’anmen incident”, but the way the pictures are presented turned out to be much more interesting than their immediate content.

Printing the pictures as negatives, and thus perhaps forcing the viewer to decode them by him/herself powerfully underlines the fact that the photos we encounter day to day, no matter if in books, newspapers or now online in blogs and the Facebook, are the result of a process controlled by someone. The final shape of photos is thus no longer strictly bound to reality, the way a negative is. This is no new development, for also in analog (or chemical) photography, the negative needs to be processed to become the final print or photograph. The question of authenticity and truthfullness has thus been discussed as long as photography exists.

It has become somewhat acute again in the general photographic public over the last few weeks, following the discovery that renowned National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry (his most famous picture is the portrait Afghan Girl) used post production techniques (i.e. Photoshop) to change the shape (and thus also content) of some of his pictures, from adjusting small details to even removing or adding persons to a picture. This sparked a wider debate in the photographic circles on the standards to which photojournalism and photography in general are held accountable to or should be held accountable to. Finally McCurry had to acknowledge he is no longer a photojournalist, but a “visual storyteller” on the page of Time Magazine.

Encouraging the viewer to use his/her smartphone for this decoding is a spark of genius. Not only is it the tool with which most photographs are produced now, its ubiquity also makes it the way through which most social unrest and protests are percieved today. In other words: if new demonstrations were to happen on Tian’anmen square, the tool they would be recorded with would surely be the smartphone, like it has happened with the Umbrella Movement of 2014 in Hong Kong, for example. Viewed through the smartphone, the pictures in this book gain an uncanny topicality, removing the historical distance to what happened in China during the summer of 1989 and keeping it alive and present. I feel deeply moved by this book and recommend everyone to take a look inside if you havn’t done so already.