Xu Yong’s exhibition shown in Hamburg, Germany from February 11 to March 16, 2019

This year’s June will see the 30th anniversary of the deadly suppression of the 1989 Chinese student movement. The movement represents the peak of China’s gradual move towards openness and social liberalization in the 1980s, its untimely, violent end was a traumatic rupture of civilization which China had last experienced during the infamous “Great Cultural Revolution” of the late 1960s.

Since then, the subject of the student movement has become taboo in China, the taboo enforced both online and offline, targeting “professional” dissidents as well as common relatives of victims of the military crackdown.

To do our part in keeping memory and awareness of this turning point in Chinese history alive, the Hamburger Sinologische Gesellschaft (Sinological society) advanced the idea of having an exhibition of Xu Yong’s negatives, eventually implementing the exhibition in cooperation with the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Hamburg (Center for political education), as well as the Bücherhallen Hamburg (Public libraries). It was decided to hold the exhibition from the middle of February to the middle of March.

My part was the task of curating the exhibition, which gave me a chance to get in contact with Mr. Xu, to work out the details of the exhibition in a half-year long process of deciding on the final shape of the artworks as well as their presentation in the exhibition alongside information about the student movement and the artist, among other things.

Xu Yong

Mr. Xu (*1954) is an internationally acclaimed fine art photographer based in Beijing. With more than ten published photobooks under his belt, and being represented by international galleries, he does not need to pursue a project like this just for shock value or the publicity. Presenting the negatives to the public (which he originally did for the first time in 2014) as a form of historical testimony is a matter dear to his heart.

Many of Xu’s earlier photographic artworks, among them his photos of Beijing’s Hutongs from the 1980s, published in 1989, already touch upon the passage of time, or photography’s relationship with time.

The NEGATIVE/SCANS are the culmination point of this pursuit. They were taken by Xu, presumably without “artistic intention”, when he was 35. He had left the Beijing Advertising Company, where he worked as a photographer, the year before. In 1989 he had started his own company and at the same time began to exhibit his own art photography. Such was his situation, when the student protests began to unfold in the middle of April.

30 years later, Xu Yong has already carved out his place in the Chinese art scene. The publication and exhibition of the negatives as an artistic statement by Xu, now 65 and looking back on a successful career, is at the same time both a brave jab at history and the forces shaping it, as well as a symbolic return to his beginnings as an artist. The passage of time itself integrates the author Xu into his artwork, transforming his role from that of a witness in 1989 to one of a conceptual artist in 2019.

The Artworks

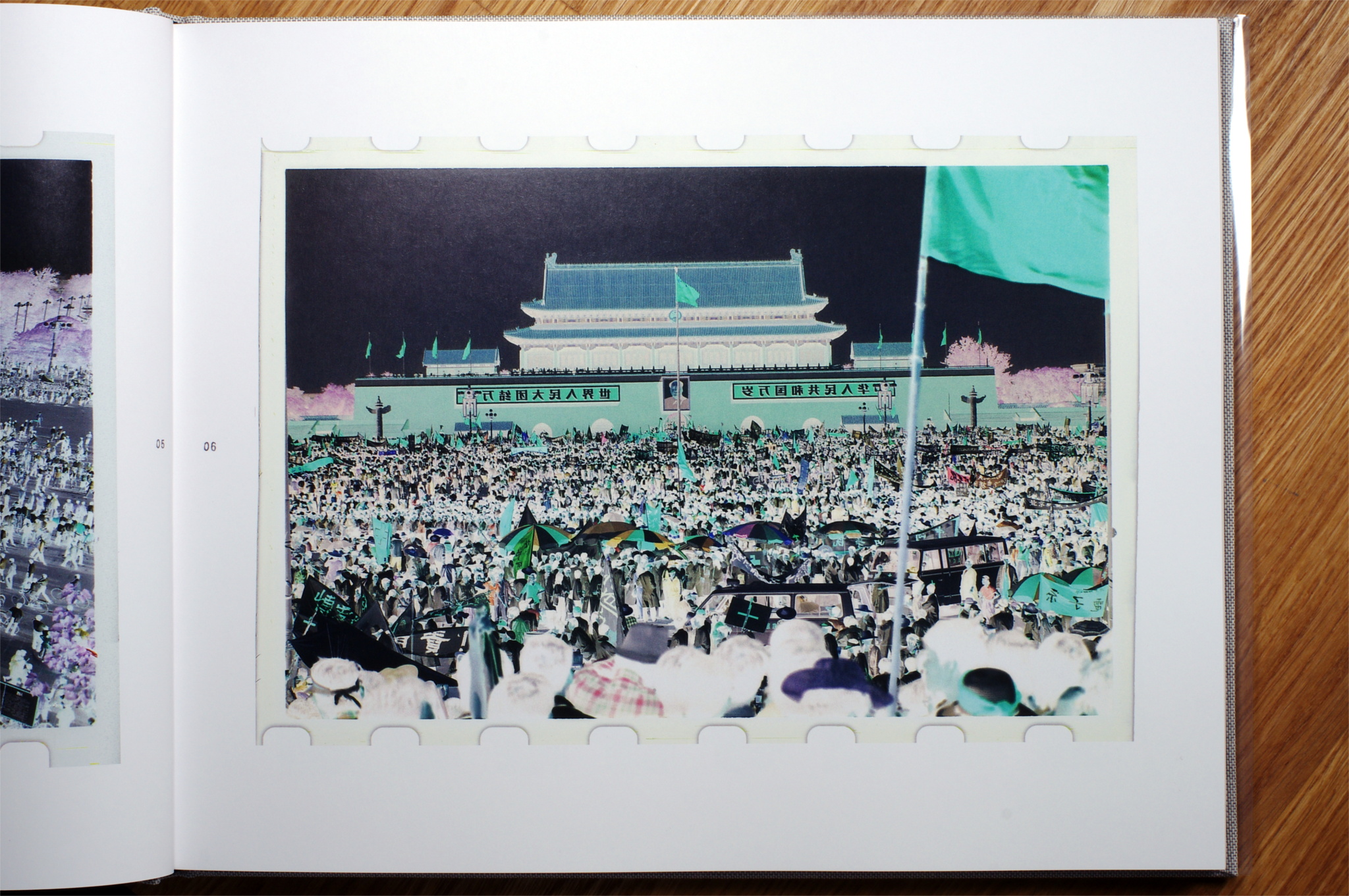

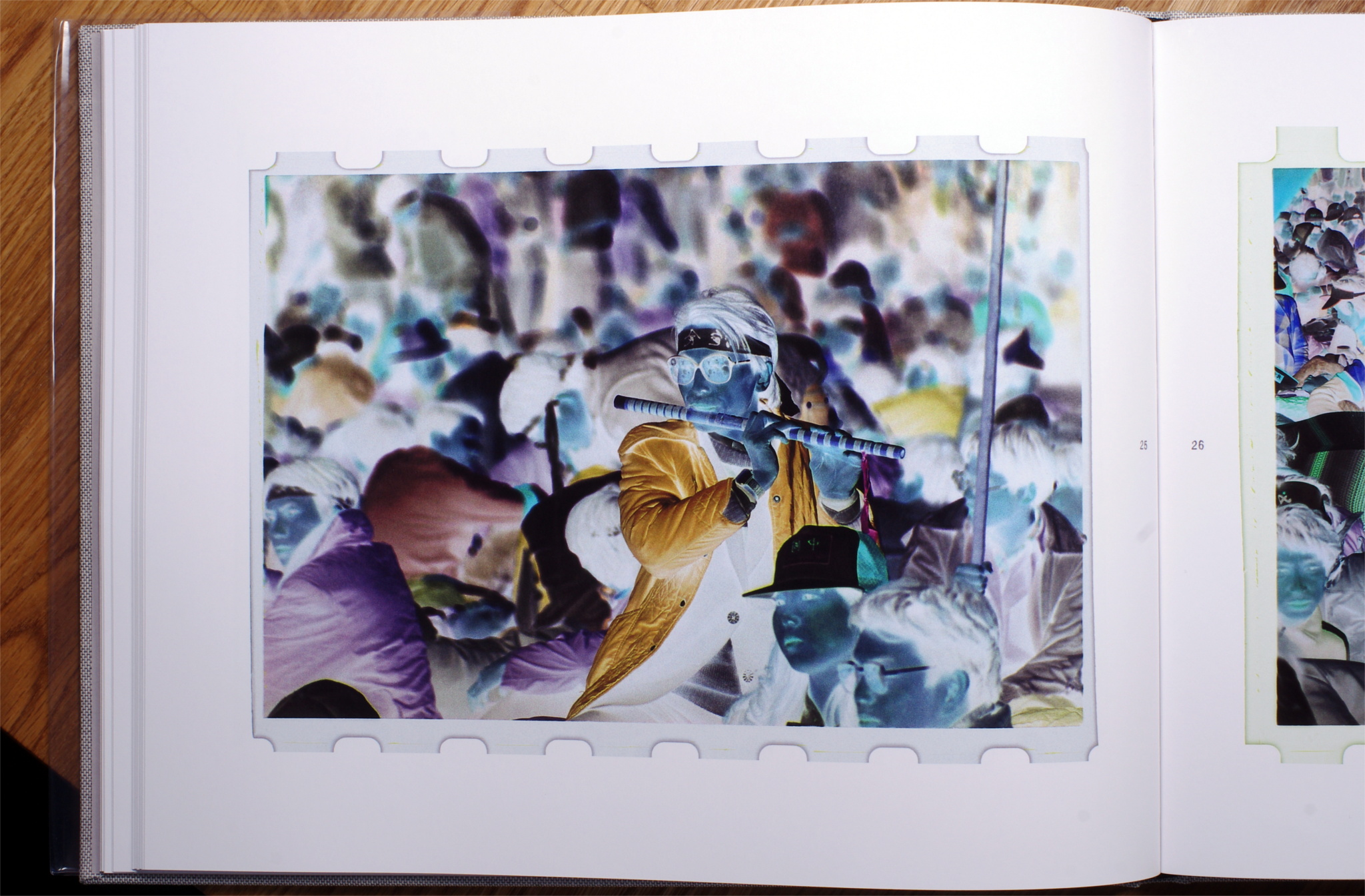

The colors of these negatives, which I exposed 30 years ago and kept deep down in some drawer, are slowly fading away. Due to the circumstances, they cannot be exhibited as regular photos. Because of this, I used the method of digital scanning to capture the material form of the negatives, which is almost like recording the photographic records of that year a second time.

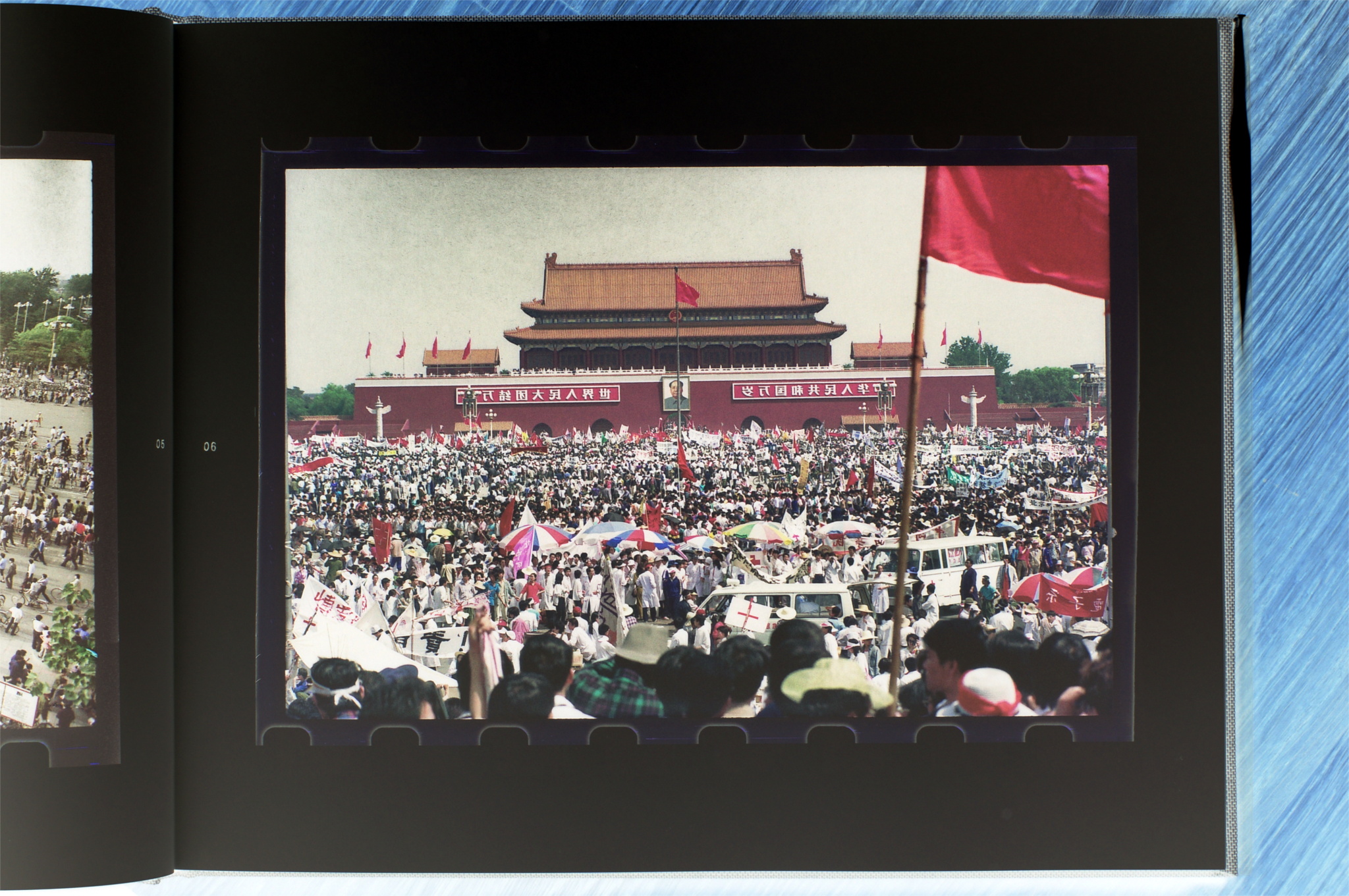

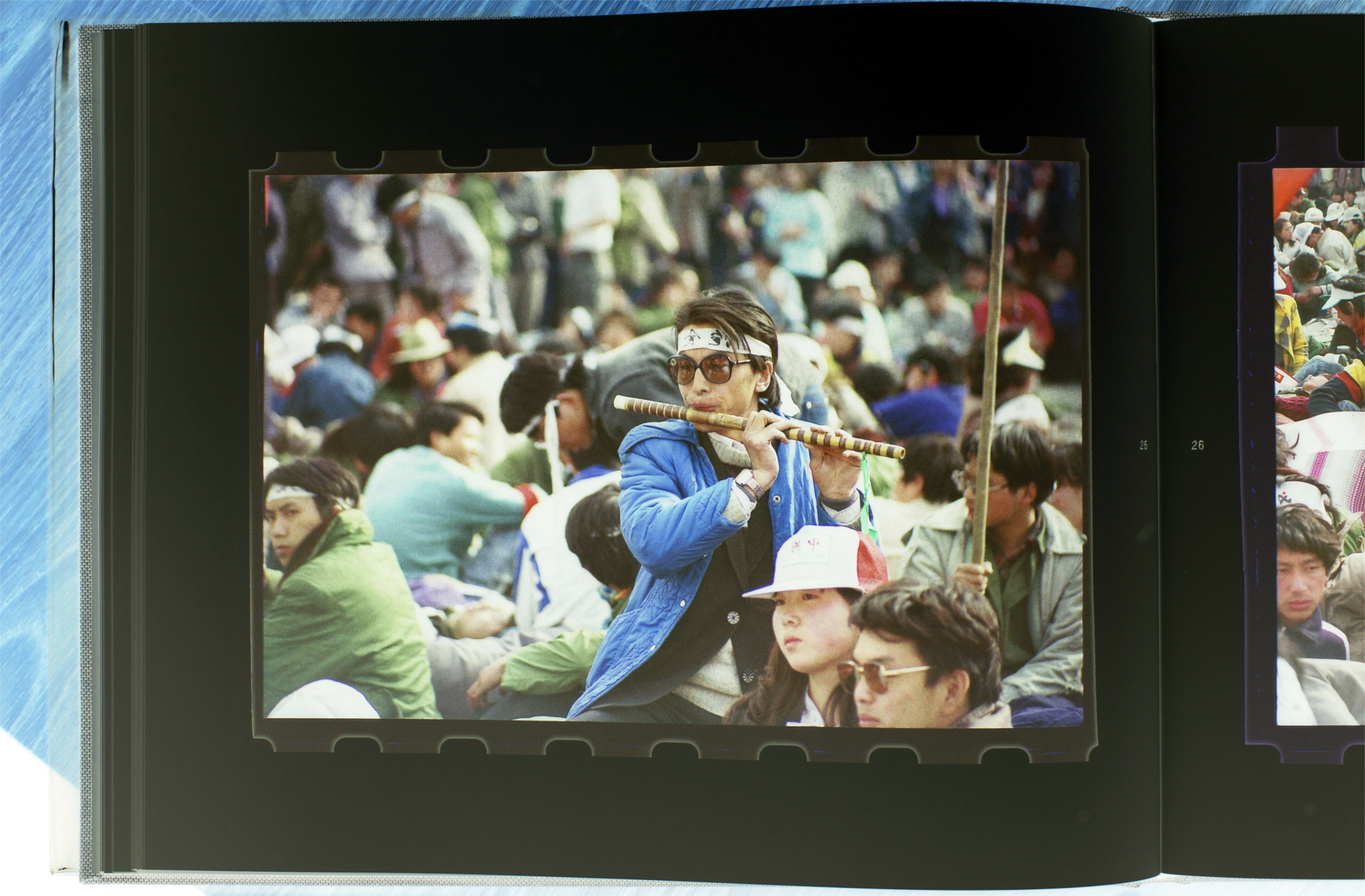

The pictures contain the traces of the oil used in the drum scanner. These traces are – just like the images on the film – the most direct proof of the uniquity of our world. The pictures appear inverted, because they have not been corrected, but the technological progress allows us to transform the pictures into their correct form, by using the digital devices we constantly carry with us.

As far as I am concerned, the most important message of these artworks is the form of the negatives in itself. It expresses what I want to express. Maybe it can prompt the viewers to reflect on the essence of photography and the relationship of the film age and the digital age, especially in China.

— Xu Yong

The 20 artworks on display are reproductions of snippets of 35mm color film in their raw, negative shape, enlarged to 60cmx60cm. Using a properly set-up smartphone, the viewer can reverse the negative colors and see the “true” historical picture inscribed in the material artifact of the film strip.

Compared to the negatives already published by Xu in book form in 2014, the shape of the negatives exhibited in Hamburg differed slightly: This time the scans of the negatives showed the film base around the picture area of the film, including sprocket holes and oil traces from the drum scanner used to digitize the negatives. This alternative shape was suggested to Mr. Xu by me, hoping to strengthen the perception of materiality of the negatives in the shape of the artworks.

The name of the group of artworks displayed in the exhibition was accordingly extended to “NEGATIVE/SCANS”, to cover the difference in regard to the “NEGATIVES” already published in 2014.

The Exhibition

The exhibition was displayed in the entrance area of the central library of Hamburg’s public library system. While it is an unusual location for an art exhibition, its daily average of around 4000 visitors from all walks of life, who would pass the exhibition on their way into the library, ensured a high visibility of the artworks and the issue of the student movement of 1989. In theory, about 120.000 visitors of the library would have had the opportunity to see the exhibition while it was on display, but of course it is impossible to say how many of those took a closer look.

From my personal point of view, when I sometimes went to the library to check up on the exhibition, every single time there were people taking a closer look at the artworks. The central library also reported a Chinese gentleman had contacted them to tell them that the Chinese characters on the banners of the demonstrators in the artworks were all wrong, showing up as mirror images of the normal characters. This mirror image is of course an intentional part of the form of the artworks, but I’m glad someone even noticed and took the time to ask.

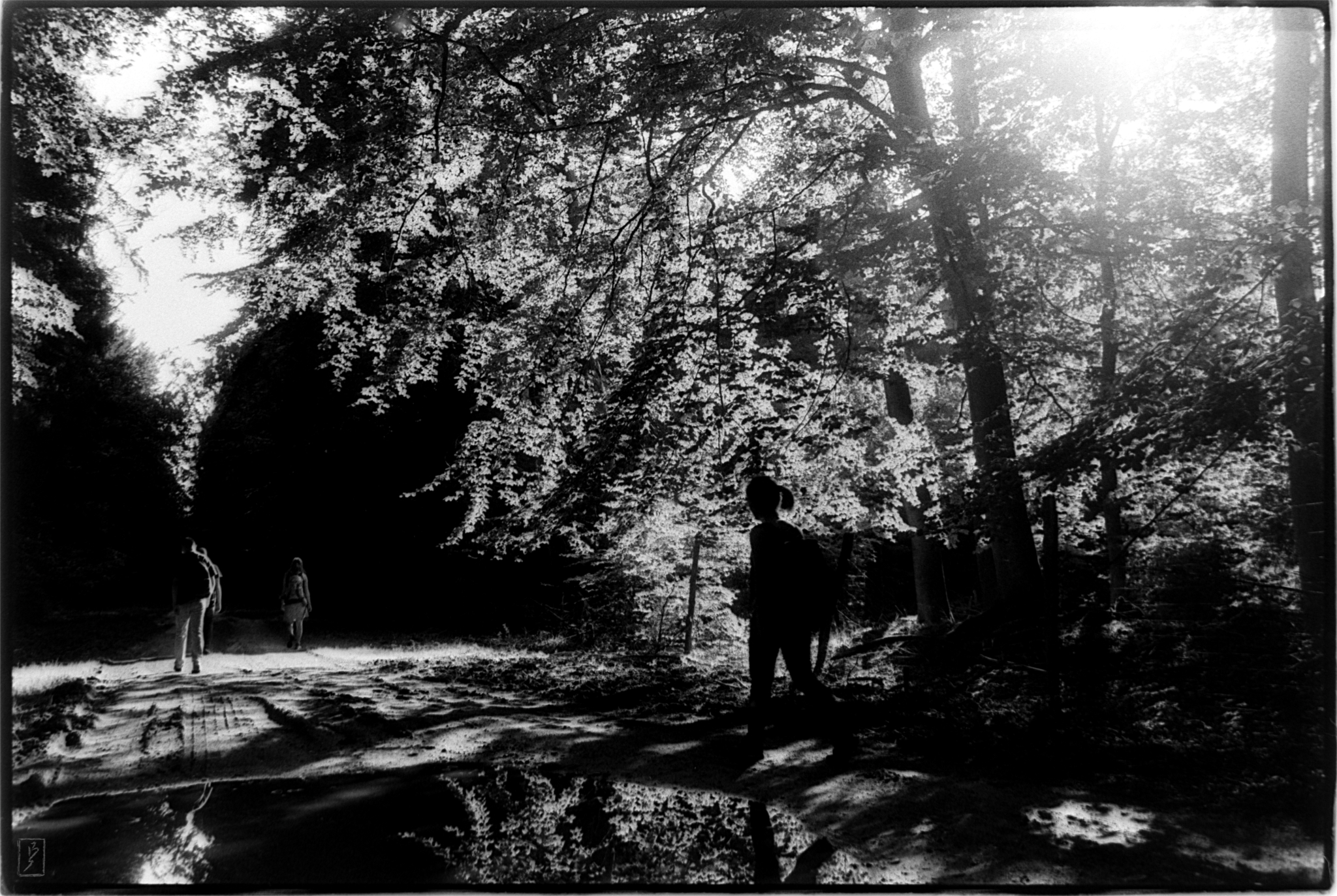

For the end I saved a little practical joke: The picture below is a scan of a negative, which I — exposing Fomapan 400 ISO film through a 1:2.8/55 Micro-NIKKOR — made of one of the artworks in the exhibition. Looks like you don’t necessarily need a smartphone to decode the images. On a film negative, the negative shape of the artworks is reverted to a positive image too.

Perhaps the choice of medium through which we engage with historic images is not all that important after all, the importance is in the engagement with the images themselves.